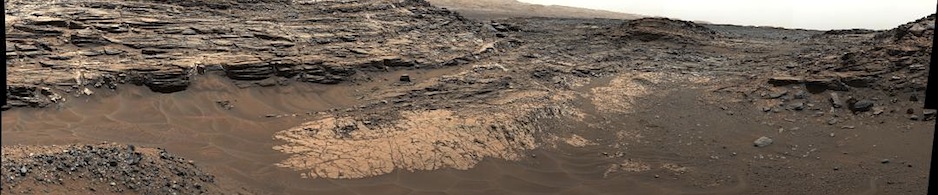

Gale Crater, the landing site for NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory rover (named Curiosity), contains a 5-kilometer (3-mile) high stack of sediments that was the reason for sending the the rover there.

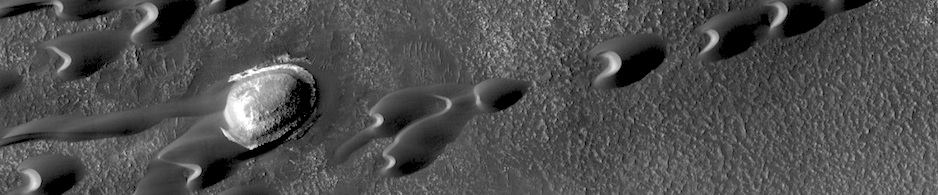

DIRTY SNOWFALLS. Repeated deposits of dust mixed with ice or snow could have built up the giant mound in Gale Crater (and other craters with similar mounds). The process resembles that which scientists think constructed the Martian polar caps. (Image is figure 2 from the paper.)

How did the giant mound form?

Dirty snow and ice, say Paul Niles (NASA Johnson Space Center) and Joseph Michalski (Planetary Science Insitute, UK). Presenting their research (PDF) at the 43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas, the scientists argue that the mound is the residue of countless layers of snow, ice, and sediments deposited in Gale by repeated climate cyles.

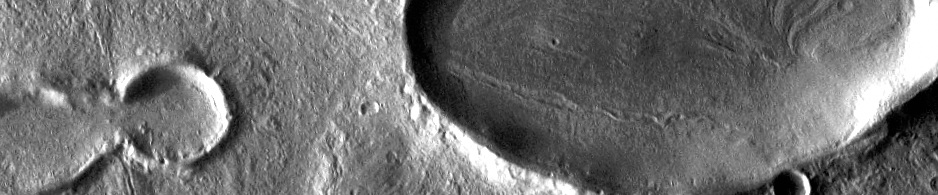

In essence, they say, the Gale Crater mound is similar in type and origin to the layered deposits found in both Martian polar caps.

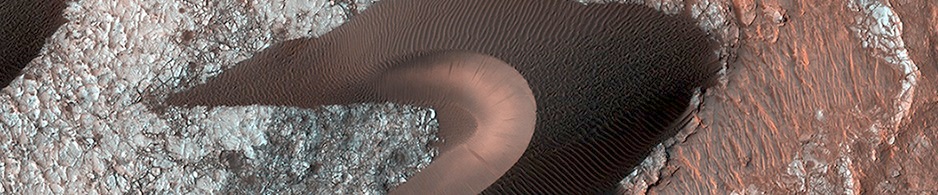

As they reconstruct Gale’s history, they say the crater formed about 3.55 billion years ago. Some time afterward, it was filled with dust, ice, and sulfur-rich aerosol particles. This process, interrupted by episodes of erosion, occurred repeatedly as the Mars’ rotation axis cycled through many changes in inclination. These drove changes in climate operating over millions of years.

Sediments, especially the older ones lower in the mound, were recycled and reworked. Deposits of snow and ice within the mound evaporated into the atmosphere, letting the dusty layers settle and become more compact. Some ice likely remains in the mound today. As the stack grew, trapped ice and water combined with the minerals in the dust to form sulfates and clays, as seen today.

From time to time, wind erosion removed parts of the mound, then new deposits arrived, draping over older ones to leave sloping and intersecting layers.

“Curiosity will make several observations to test this hypothesis,” the researchers say. “Similar to Meridiani Planum, the sediments should be fine-grained with chemical compositions that closely resemble martian dust.” In addition, they do not expect Curiosity to find beds of pure carbonates, sulfates, or other salts which would point to a standing lake or other body of water in Gale.

But they do expect to see “abundant unconformities, which suggest many multiple cycles of deposition and erosion.”

The scientists of the Mars Science Laboratory mission have informally named the Gale Crater mound as Mount Sharp. The name commemorates Caltech geologist Robert P. Sharp (1911-2004), a founder of planetary science, influential teacher of many current leaders in the field, and team member for NASA’s first few Mars missions.