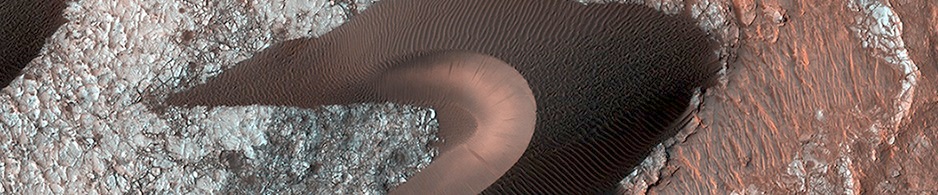

Jets of gas erupting in the springtime from beneath slabs of carbon dioxide ice at the Martian south pole was a dramatic finding in 2006. It explained the mysterious “spiders” which came and went each year. Now the same mechanism working on a smaller scale has been proposed to explain grooves that appear on north polar sand dunes.

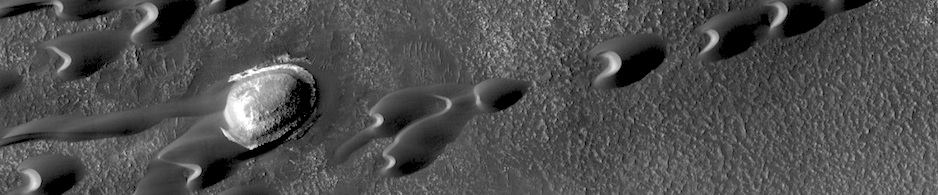

CRYO-VENTS on north polar dunes shoot sediment into the air from under a thin CO2 ice layer. The escaping gas erodes furrows under ice. (Image is taken from the online abstract.)

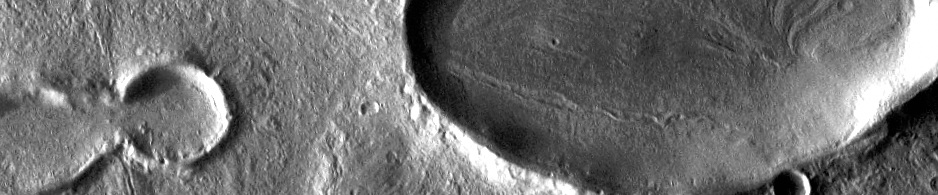

Mary Bourke (Trinity College Dublin and Planetary Science Institute) reported on the discovery (PDF) at the 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas. Her report presented evidence from HiRISE images showing long furrows on sand dunes.

“These are shallow and narrow forms which can extend up to 300 m (1,000 feet) along the dune surface,” she says. The furrows are typically about 25 centimeters (10 inches) deep and some 1.5 meters (49 in) wide. They may be straight or highly sinuous, and network patterns vary — radial, rectilinear, tributary, and distributary all occur.

“These are important dune surface features,” she explains, adding that they can be seen almost all HiRISE images of north polar dunes and have been detected on south polar dunes.

Details of the furrow patterns – such as radiating upslope – indicate that they are caused by something flowing, but not simply downhill under gravity. “This suggests that the formative fluid is likely to be a pressurized gas,” Bourke explains.

Adapting the model for south polar gas jets to the smaller scale of the dunes, the same basic process appears to be at work, she says, calling the process “cryo-venting.”

It works as follows. When north polar autumn descends into winter, a seasonal CO2 ice layer forms on the north polar dunes. As spring sunlight arrives, it triggers the CO2 to begin sublimating at the bottom of the ice layer, raising the gas pressure underneath the seasonal ice. The gas buildup lifts the overlying ice, flexing it, and causing stress cracks.

As cracks open, gas escapes, along with sub-ice sand and sediment caught up in the gas. The sediment flows erode the furrows, and the jetted sand falls back in fans, spots, and grain flows on top of the ice. When the ice disappears, all that’s left are the furrows.

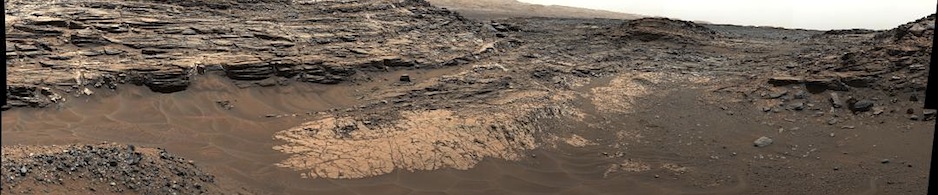

Gas jets are spaced roughly 5 meters (16 ft) apart, and cryo-venting carries significant amounts of sediment, Bourke notes. She estimates that the process can move the volume of a small dome dune (about 500 cubic meters) each season.

“The cryo-venting lasts for about 40 sols [Martian days],” Bourke says. And unlike the south polar gas jets, the dune vents don’t erupt at the exact same locations on the dunes year after year. This could be due to seasonal variations in both the dune and the ice cover alike.