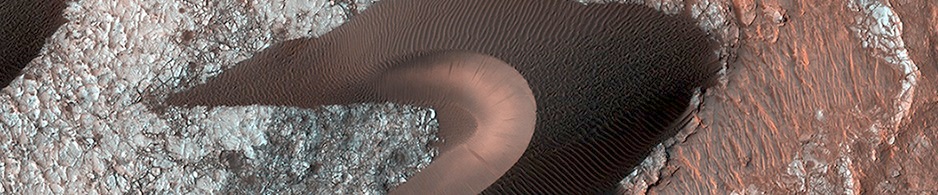

Sand — in wind-blown ripples, drifts, and dunes — lies all over Mars. But it poses a puzzle because the current atmosphere is too thin (less than 1% of Earth’s) to move that much sand around. So researchers in the past have proposed that most of the dunes are fossils, put in place during some previous era with a denser atmosphere.

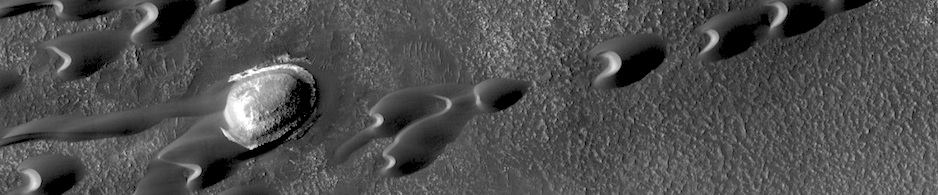

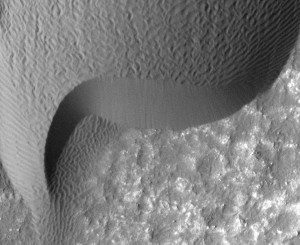

MOVING SANDS IN HERSCHEL CRATER. A rippled dune front in Herschel Crater moved an average of about two meters (about two yards) between March 3, 2007 and December 1, 2010. The ripple pattern on the dune surface changed completely during the interval. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Ariz./JHUAPL.

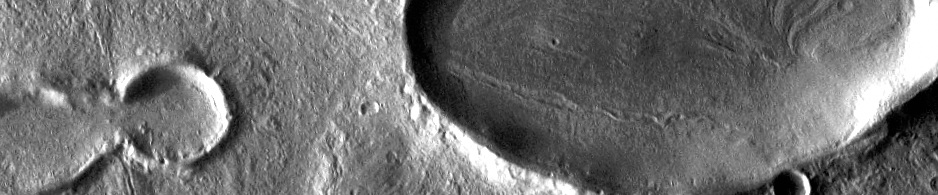

Not so fast, says a group of scientists led by Nathan Bridges (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory). Writing in the journal Geology, they examined sand dunes and ripples in dozens of locations with high-resolution images from the HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

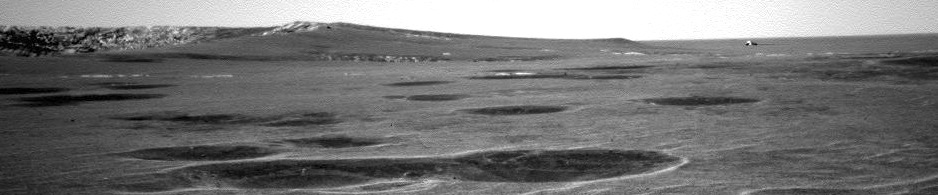

The study involved pairs of HiRISE images, with one to two Mars years (one Mars year lasts 679 Earth days) elapsing between them. Migration of sand ripples was detected in Nili Patera, Kaiser Crater, Herschel Crater (see this animated GIF), Matara Crater, Proctor Crater, and Meridiani Planum. (Future studies will continue the observational baseline.)

“We found that many sand ripples and dunes across Mars show movement of as much as a few meters per year,” the team writes. “This demonstrates that Martian sand can migrate under current conditions.”

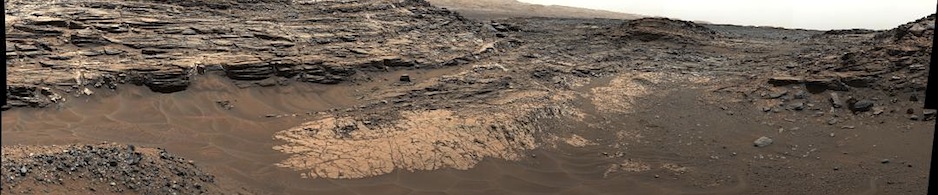

Some changes they observed contradict previous interpretations. For example, in earlier images made with the MOC camera on Mars Global Surveyor, the dunes in Herschel Crater appeared to have a grooved texture. Scientists interpreted this as cemented sand that was undergoing abrasion. However, in the HiRISE images, the texture is seen as complex sets of intersecting ripples that change over time.

The key to the process, the researchers explain, is that most sand movement is probably driven by wind gusts. These are not figured into existing global wind circulation models which have generally coarse resolution.

“A past climate with a thicker atmosphere is required only to move large ripples that contain coarse grains,” they say.