Scientists have long suspected that ancient Mars had a thicker atmosphere and temperatures warmer and far more habitable than at present. But modelers have difficulties making the numbers come out right, even when they assume a much thicker carbon dioxide/water vapor atmosphere than today’s.

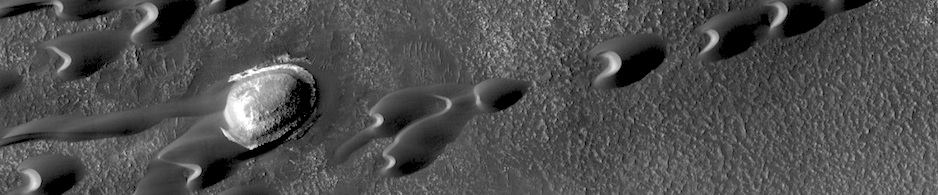

IF EARLY MARS had a little nitrogen in its atmosphere, temperatures in the Noachian would have been warmer and habitability greater despite a fainter Sun, says new modeling research. (Sunset over Gusev Crater by Mars rover Spirit; NASA image)

Maybe adding some nitrogen (N2) to the picture can solve the problem, says a team of researchers led by Philip von Paris (DLR, Berlin). Writing in Planetary and Space Science, they report on 1D modeling experiments that assumed a small increase in nitrogen in the early Martian atmosphere. Their modeling also included cloud-free conditions, a faint Sun, and the effects of solar radiation on atmospheric nitrogen.

“Results suggest that increasing N2 partial pressures could lead to significant surface warming,” they note, “without accounting for CO2 clouds or additional greenhouse gases.”

Starting with models of CO2 atmospheres that range in pressure from 0.02 bar (of the same order of magnitude as the current value of 0.006 bar) up to 3 bars (about 500 times the current value), the researchers injected up to 0.5 bar of nitrogen. (Currently the Martian atmosphere has 0.0002 bar partial pressure of nitrogen.)

The results from the increase of nitrogen showed a warming of only 13 kelvin (24° Fahrenheit), which the scientists admit is not much. “Even at this N2 partial pressure, global mean surface temperatures remained below 273 K, i.e. the freezing point of water,” the team acknowledges.

However, the team says, 3D model studies (by other researchers) of early surface temperatures that did not contain nitrogen show that local temperatures in early times may not have been far below 273 K. “Our results imply that the presence of atmospheric N2 could have led to almost continuously habitable mean surface conditions in some regions,” they note.

In addition, the scientists found that adding nitrogen to the early atmosphere not only warmed the surface, but also boosted (by about six times) the amount of water vapor in the air. “This indicates,” the team says, “that precipitation as rain or snow might also increase upon increasing the nitrogen partial pressure.”

Looking ahead, the researchers note that, “detailed studies of the outgassing history, impact delivery, and atmospheric escape of N2 are needed to assess whether high N2 partial pressures could be consistent with the late Noachian period.” And they intend to explore what an increase in nitrogen would mean in regard to liquid water at the surface.