When geological forces open a crack in bedrock, molten magma can squeeze in and widen it, after which the magma cools and hardens in place. The result is a dike, and such features let geologists delve into an outcrop’s history by exposing rocks of different compositions and ages.

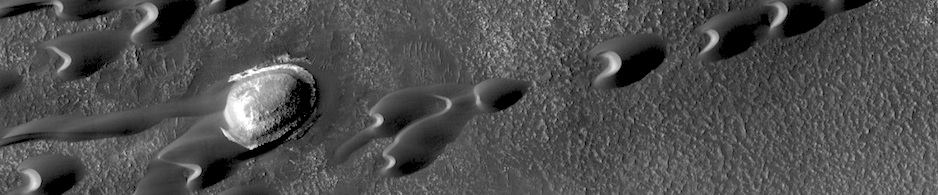

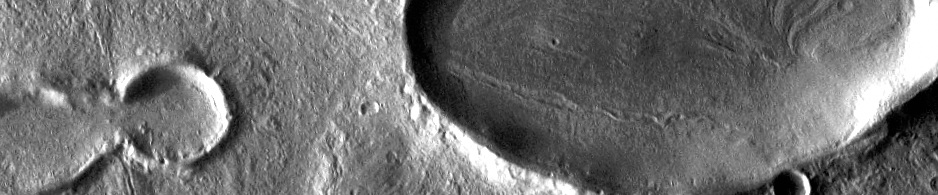

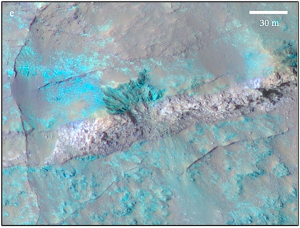

PLUGGED CRACK. An igneous dike 30 meters (100 ft) wide cuts across part of the floor of Coprates Chasma in Valles Marineris. The dike, different in composition and texture from its surroundings, is flanked by smaller-scale ridges and fractures. The false-color image is part of HiRISE frame ESP_013903_1650; the bluer areas are low-calcium pyroxene bedrock into which the dike has intruded (figure 2e from the paper).

A team of scientists led by Jessica Flahaut (ENS Lyon/Université Lyon 1) has used images from the HiRISE camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) to discover and study dikes in the lower walls of Coprates Chasma, part of the vast Valles Marineris canyon system. Their report appears in Geophysical Research Letters.

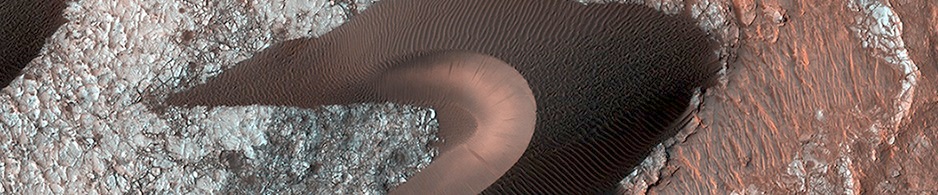

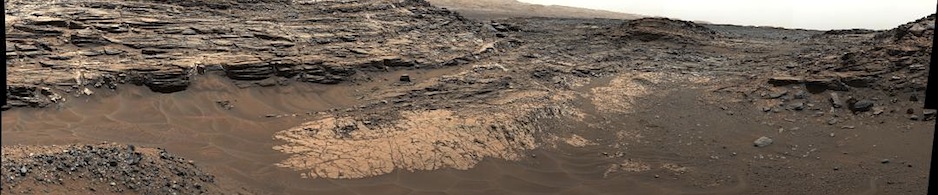

The canyons in Coprates cut 7 to 10 kilometers (23,000 to 33,000 feet) deep, exposing a thick section of crust dating back to the Noachian, the oldest period of Martian geologic history, roughly 4.1 billion years. The dikes appear in the lowest part of the walls, and their orientation suggests they are linked to either the canyons’ formation by tension and collapse, or that they intruded through pre-existing fractures and faults.

Using mineralogical data from MRO’s CRISM spectrometer covering some of the dikes, the team identifies the dike material as a large-grain olivine-rich basalt. Olivine is an easily weathered igneous mineral.

While numerous dikes have been mapped, the team says the list is not complete. “More dikes are likely to be present in this area,” they note. “But they’re difficult to identify and characterize as the walls have experienced mass-wasting, gravity-induced slumping, and tectonic erosion.”

Looking at the big picture, the scientists favor two scenarios for how the dikes relate to Valles Marineris. One scenario sees the dikes as the root source of the volcanic layers, several kilometers thick, that form the upper half of the canyon system. If the magma in the dikes rose through vertical fractures, then spread out horizontally, the dike rock would merge indetectably into the layers themselves — they would in fact be the layers.

In the second scenario, which the team says they favor slightly more, the canyon system opens up due to tectonic and volcanic forces associated with the rise of Tharsis, a region of giant volcanos just to the west. In this version, the dikes are confined to the lowest and oldest Noachian bedrock layers because they were active only in the early history of Valles Marineris. The upper layers then are the result of regional eruptions and activity from Tharsis.

In any case, they say, “The occurrence of preserved Noachian bedrock in situ, which is rare on the Martian surface, together with compositionally distinct dikes, underlines the need for future exploration in Valles Marineris.”