The Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity has found thumb-wide veins of gypsum in a rock layer at Cape York, the Endeavour Cater rim segment where it will spend the coming Martian winter. The discovery was announced at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

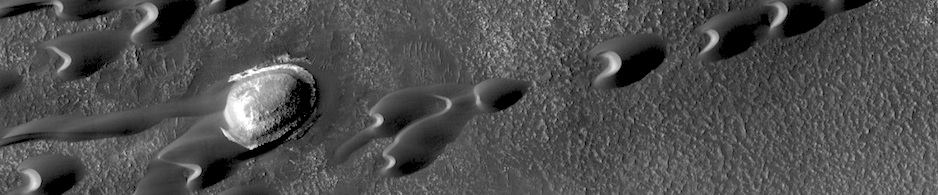

IN THE VEIN. A light-colored vein of what is likely water-precipitated gypsum sticks up a new millimeters above the soil at Homestake, an exploration site near where Opportunity will spend the Martian winter. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell image)

The gypsum is, in the words of MER principal scientist Steven Squyres (Cornell University), “the single most bulletproof observation for water that Opportunity has seen.”

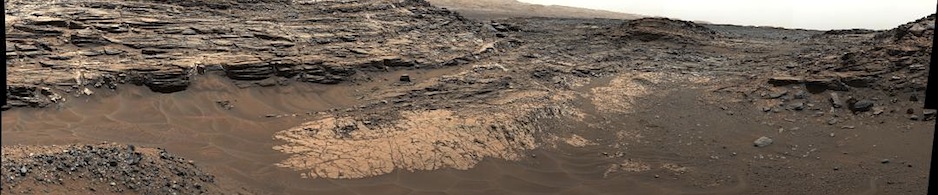

The rover first spotted the light-colored veins in an area of bedrock as it approached Cape York in August 2011. However, project scientists were eager to examine the rocks of the Endeavour rim, and simply noted that the veins looked interesting and drove onward.

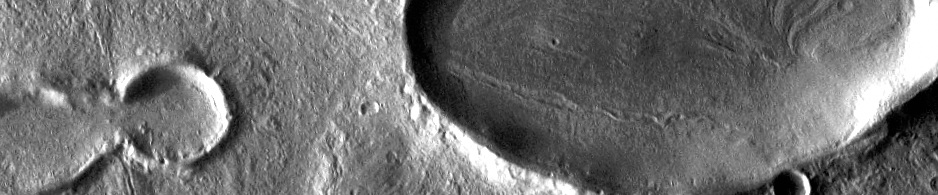

The rim rocks proved unlike any seen before by Opportunity in the nearly eight years since it landed, in January 2004.

“When we got to Cape York,” says Squyres, “it was like starting a new mission all over.” The Cape York rim rocks include several — dubbed Tisdale, Chester Lake, and Transvaal — that bear clear hallmarks of the ancient impact that made Endeavour. These include pieces of broken rock embedded in a matrix of once-molten impact melt.

The impact-altered rocks collectively will be called the Shoemaker Formation when formally described in the geological literature. Earlier, the project named the high ground running down the spine of Cape York “Shoemaker Ridge,” to honor Eugene Shoemaker who was one of the founding fathers of planetary science.

After studying the impact-related rocks, scientists drove Opportunity northward along a bench-like layer to a site dubbed Homestake. Here was another light-colored vein, about as wide a thumb and standing a few millimeters above the soil. The scientists drove the rover’s wheel over the vein several timnes, then deployed the APXS spectrometer on it. This said the vein was full of calcium and sulfur, which pointed to gypsum, the commonest sulfate mineral that precipitates from water.

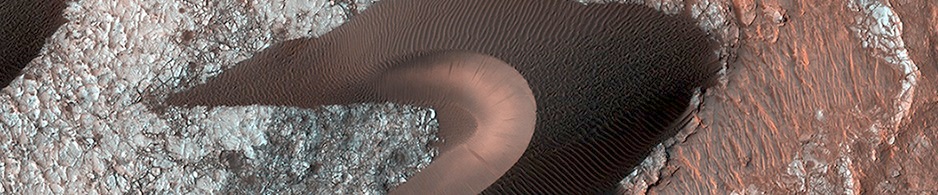

Big impacts, such as that which created the 22-kilometer (14-mile) wide Endeavour, trigger hydrothermal activity in the target rock. Existing groundwater below the crater creeps upward into fractures in the crater floor and rim. The lingering heat from the impact warms the groundwater and helps it extract minerals from the surrounding rock. Carried in solution through the fractures, the minerals then precipitate when the water cools.

“We can’t say for sure it’s gypsum because the vein is too small to fill the instrument’s field of view,” Squyres says. “But we subjected it to blunt-force trauma in the name of science.”

The team plans to do further tests on it when Martian spring arrives. That is also when the team will drive Opportunity south on the eastern side of Cape York to explore the Shoemaker formation more fully.