Total solar eclipses on Earth take hours to unfold, even if totality — the brief time when all the Sun is covered — lasts just a few minutes. Almost everyone who stands in the path of a solar eclipse notes how the air and ground become cooler as the eclipse deepens.

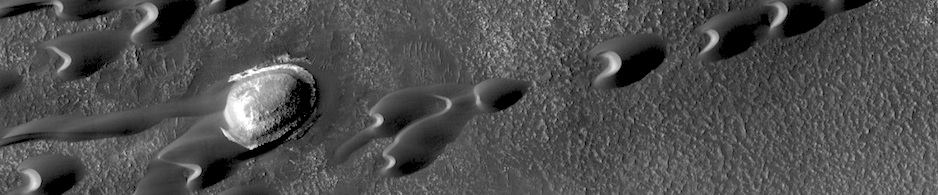

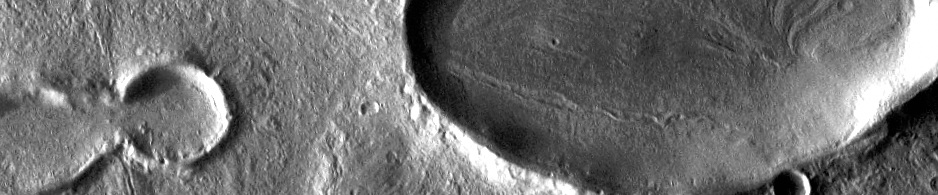

GONE WITHOUT A TRACE. Martian moon Phobos cast a shadow on the ground on November 24, 2010. At the time, the Mars Odyssey orbiter was passing overhead and imaged the shadow with the THEMIS camera at visual and infrared wavelengths. While the shadow was clearly visible (frames A and B), the moon's passage was too swift for any cooling to occur among the rocky materials on the surface. Frame C was taken during the shadow's passage and frame D was taken for reference a few days before the event. (Image taken from Figure 3 in the paper.)

Mars has no total solar eclipses, because neither Deimos nor Phobos is large enough to cover the whole Sun as seen from the surface of Mars. Yet both fast-moving moons do cross the Sun’s face as seen from the ground, causing partial eclipses. Phobos, the larger moon, produces eclipses that cover as much as 38 percent of the Sun. How strong a thermal effect does the surface experience during a Martian solar eclipse?

No measurable surface cooling, say Sylvain Piqueux and Philip Christensen (both Arizona State University) in a recent paper published in Geophysical Research Letters.

“On November 19, 22, and 24, 2010,” they write, “the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) onboard the Mars Odyssey spacecraft acquired a set of visible (VIS) and infrared (IR) images of the Martian surface during three transits of Phobos.”

During these events, which occurred around 4:30 pm local time and lasted 31 seconds each, about 20 percent of Sun’s disk was eclipsed. This reduced the incoming solar flux by a similar amount. While Phobos cast a clearly seen shadow on the ground (as imaged at visual wavelengths), the darkness and cooling came and went too quickly to change the temperature of the surface.

“In all three events,” the scientists say, “no obvious surface cooling is measurable.” This was despite the observations targeting the trailing edge of the Phobos shadow, where temperature drops would be the largest. THEMIS, they note, could have detected any temperature drop greater than half a kelvin, or about 1 degree Fahrenheit.

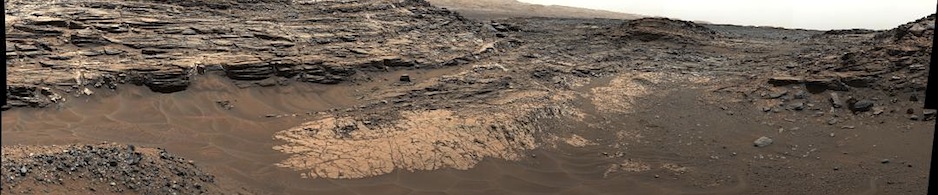

So what does this say about the Martian surface? The new results indicate that surface materials at the observation sites are somewhat rocky and have no significant blanketing by dust. (Dust heats up and cools off quickly, while harder materials — sand, gravel, grit, and rocks — change temperature more slowly.) This finding suggests that any dust present was less than a millimeter thick, which agrees with earlier work that studied similar surface geological units.

The team says, “Phobos shadow observations can contribute to bridge the gap between high-coverage, low-resolution orbital data and punctual-coverage high-resolution surface-based data obtained by rovers and landers.”